Dahlma Llanos-Figueroa

Dahlma Llanos-Figueroa was born in Puerto Rico and raised in New York City. She is a product of the Puerto Rican communities on the island and in the South Bronx. As a child she was sent to live with her grandparents in Puerto Rico where she was introduced to the culture of rural Puerto Rico, including the storytelling that came naturally to the women in her family, especially the older women. Much of her work is based on her experiences during this time. Llanos-Figueroa taught creative writing, language and literature in the New York City school system before becoming a young-adult librarian and writer. The hardcover edition of Daughters of the Stone was shortlisted as a 2010 Finalist for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize. Her short stories have been published in anthologies and literary magazines such as Breaking Ground: Anthology of Puerto Rican Women Writers in New York 1980-2012, Growing Up Girl, Afro-Hispanic Review, Pleaides, Latino Book Review, Label Me Latina/o, and Kweli Journal. She lives in New York City.

Featured Work

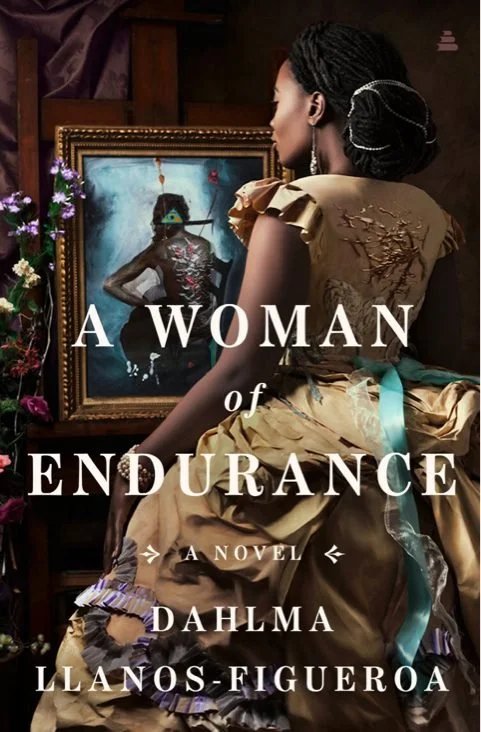

A Woman of Endurance

Combining the haunting power of Toni Morrison’s Beloved with the evocative atmosphere of Phillippa Gregory’s A Respectable Trade, Dahlma Llanos-Figueroa’s groundbreaking novel illuminates a little discussed aspect of history—the Puerto Rican Atlantic Slave Trade—witnessed through the experiences of Pola, an African captive used as a breeder to bear more slaves.

A Woman of Endurance, set in nineteenth-century Puerto Rican plantation society, follows Pola, a deeply spiritual African woman who is captured and later sold for the purpose of breeding future slaves. The resulting babies are taken from her as soon as they are born. Pola loses the faith that has guided her and becomes embittered and defensive. The dehumanizing violence of her life almost destroys her. But this is not a novel of defeat but rather one of survival, regeneration, and reclamation of common humanity.

Readers are invited to join Pola in her journey to healing. From the sadistic barbarity of her first experiences, she moves on to receive compassion and support from a revitalizing new community. Along the way, she learns to recognize and embrace the many faces of love—a mother’s love, a daughter’s love, a sister’s love, a love of community, and the self-love that she must recover before she can offer herself to another. It is ultimately, a novel of the triumph of the human spirit even under the most brutal of conditions.

Five Questions for Dahlma Llanos-Figueroa

-

Telling the story-not told is what gets me to my computer every day. Our ancestors’ stories are left out of the national dialogue. They sacrificed so that I can tell what has been omitted or misrepresented.

-

When I think of all that our ancestors went through, the men, certainly, but especially the women, during enslavement, the only word that comes to me is endurance. I acknowledge the violence and brutality because only by understanding that can you understand what it took to survive it.

-

Characterization always comes first for me. How can you bring the reader into the world you create, if they don’t understand or care about your characters? They must become as real to the reader as a member of their family or even of themselves.

-

When writing one torture scene in particular, I got up, congratulated myself on a job well done and then threw up for three days and had to be hospitalized. In retrospect it was worth it. I can’t take my readers there if I don’t go there myself. I didn’t dwell on the torture scenes, but they were necessary to understand the character and the story.

-

Toni Morrison is my spiritual and literary godmother. She gave me permission to write my story, my way and not worry about critical acclaim. I came to understand that the people who needed to see themselves on the page deserved absolutely honesty and truth. Enough of stereotype and caricature. I write the truth of my world and trust that enough people will see themselves in it. Some people will get a glimpse of the story-not-told and understand the underlying common humanity in all of us.

Isabel Allende opened the door to family secrets. She also uses the mystical nature of our Latino cultures to infuse the story with meaning. Those were not found in much of our contemporary literature. Some may call it ‘magic realism’, but I think of it as mysticism or spirituality that informs the lives of enslaved or colonized people. That style of blurring the line between objective reality and with a sense of the mystical may have been labeled by Western society as a German fine arts construct, but indigenous people all over the world have left us proof that their way of coping with a sometimes-unbearable reality is to fracture their experiences and the environments in which they were forced to live.

Dolen Perkins-Valdez is a master of the neo-slave narratives. Her first two novels, Wench and Balm, take the reader to an often surprising, complex and nuanced world of African Americans during and just after the period of enslavement. Her characters come to life as she places them in time and place. She creates a world of the long-ago past which becomes a strong foundation on which to anchor the plot. All of these are based on a foundation of specificity. That level of detail can only be achieved through research. Her work taught me an important lesson: when writing historical narratives, research is essential in world building. Everything else rests on that.